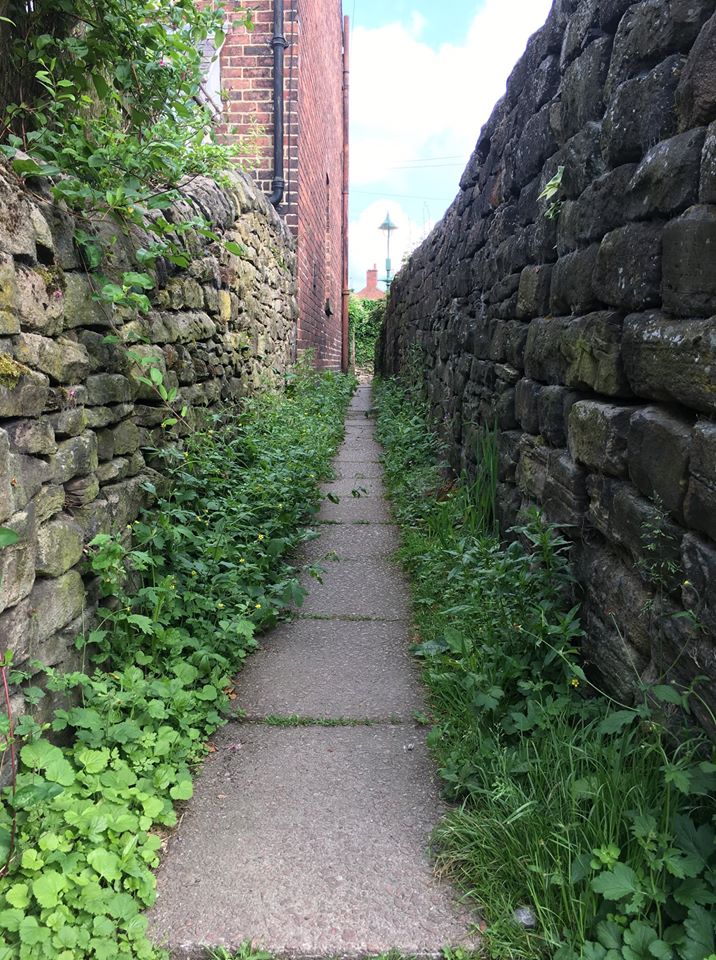

My short story Jitty has been published in Issue 41 of The Blue Nib.

JITTY

What am I? The spirit of the jitty, of all the jitties, all over this town. I expect there are more like me, in towns and cities, wherever there’s a jitty. In other places they call them alleys, ginnels, snickets, twittens, shuts. I know these names from people who pass with different accents, and say the wrong word. You can tell when someone’s from further away sometimes, even before they speak.

What sort of a thing am I? Just this, what I’m telling. The spirit of all that has passed here, through these channels, these back ways, these jitties. The trace, the track, the leaving. So I’m anxious, nervy, hurried and furtive. I’m hopeful, excited and full of desire. Then the darker meat: plotting, suspicion and deviance. But try not to judge me. I’m only the sum of my parts, which are your parts. The parts you have played, as you pass along the jitties of the town, on your way home, out shopping, or drinking, to meet with your friends, with your lovers, to follow and spy on your enemies.

Oh, I know spite and resentment, the spurned, deceived lovers tailing new couples, the fear and the hope in the breathing and voices of people who hide their love here. Not everyone comes from the jitty the same as the person who walked there and talked, stopped and waited. Met others, another, embraced and wished they could shrink back into the cracks of the walls as I can, who pass past their passing and see as they come and they go. The men wait for women wait for women wait for men wait for men wait for women wait for women wait for men wait it’s easy to stick in a cycle like that one, a loop, for a long time. Forever, I’m sure, if you don’t find the will to break out of it. A circle of words can fill all of the dark between days, between dark, between days, between dark, between days, when there’s nobody passing. But those nights are rare. The jitties draw people, invite them like lovers, inside.

Love is love in the jitty, took quick, maybe stolen. In these shaded places, some people reveal themselves. Friends enter jitties, and so friends emerge, but between, within, sometimes, they’re lovers. The touch, the kiss, the sudden swell and press of warm desire. The drunken screws, quick, clothed and hungry. Shared minutes of passion in lifetimes of guilt and denial, perhaps. Or sometimes they can’t wait, can’t carry their lust up the valleyside home, and stop here in the darkness instead, to unleash it. Laughing and pouting, up against the wall, gritstone against shoulderblades as they press together, hidden here, unknown except to me.

I’ve no wit of my own, I’m not clever. I know only what you tell me, in passing, as you pass. I expect there was a time when I didn’t use words, hadn’t learned them from you, from your fellows and forebears. I know plenty now, more than some of the people who walk here. Time’s been on my side. And stories, I know lots of stories. They’re snippets and snatches, small scraps of your lives, just the times in the narrow gaps here between buildings, the passages passed in the passage. The jitty, my realm.

I can zip about easy enough, and unseen, or at least nobody ever stops to talk to me. No, wait. That’s not true. You do get odd poets and singers, or drunkards, who say out loud how much they love this jitty. But I know they don’t mean me, they mean the stones, the steps, the way plants grow from the wallstones either side. Not me. They haven’t seen me. Come to that, I haven’t seen myself. Sight’s not my strongest sense, I’m more a feeling, smelling, hearing thing. I listen, to the wind and traffic sounds that blow and bounce from off the bricks and stones, but more keenly to the footfalls and talk of the people who pass. They speak alone, into phones or to themselves, and then some of them sing. I’ve known a good few that way, because they sing the same songs, often at night, on their way home, pulling up the valleyside between the houses, singing. One that I remember used to sing himself a song about the town:

Somebody told me you lay there like poetry:

Cotton-tied, the river’s bride, riverside the cottoned widow.

And that’s the way you promised that you’d stay,

But now you’re changing, and pushing me away.

For all the warmth in his voice, those words used to hurt. He wasn’t singing to me, although I do change, I have changed, can’t help it. But as for pushing, never! If I could catch and clutch you all to me, how I would show you my love. See there, that’s me and him both singing and sighing after the same old forever thing – all that we lose and can’t get back again.

It was a sad song, of loss and longing, but the sound of him found its way into the stones, and I feel the vibrations he left, in quiet times along these ways. He would sing of separation from the home he had known, and although I have never had a home beyond these ways, I still feel the pain of estrangement. For this is what I feel, from the world outside the jitty, the world that I know must go on all the while, but of which I hear only what wind and the walkers bring here to me.

Sometimes, it would be a long while between his visits, but my memory is very good, and when he came back with another verse, his voice heavy with drink, I caught and kept it. Here was an exile, returning infrequently, but never fully gone, not inside himself. It’s hard to leave this place, properly. It follows, and calls you back. So back you keep coming, down your days.

I share special moments in young people’s lives. The times that your parents don’t find out about. The first can of beer, shared between friends, one of whom has pinched it, warm perhaps and not unshaken, from a parent or sibling. The first cigarette, sucked at and coughed over, with friends who knew this would happen, but not that the moment might colour your view of their friendship. Shared bottles of stronger drink, before school discos from which you would later be ejected, for turning up drunk. Oh yes, I’ve heard, smelled and known all of these. I am only what you have made me – the traces of your passing. The moments of your life you left behind, here in the jitty.

And later, older, still you took these short cuts to the taverns of the town, and pulled your way back up the valleyside along the jitties, home. But still your leavings stain and scent these channels, where you couldn’t hold it in, and stopped to piss, or should have held back in the boozer, spewing what your gut could not accommodate. Dropped bottles, too, smashed in the dark. The people in the morning taught me words to describe you, but I’m sure you don’t need to hear those again, and I’m certain you’ve learned at least some of the lessons of youth.

For me, time is nothing. I know, and remember, but little is new. Different words to call alcohol, new words for men and for women, new fashions that don’t quite recapture the fashions they follow. New ways to say what you want from each other, although most of it boils down to something eternal and unified:

‘Hold me.’

Which is what I do, or what I would do if I could. I’d hold you all, my children, kids of the jitty, their mothers and granddads and all. But you pass, and the price of my timeless long life is that you move beyond, take a place in the world, and I cling to the scraps that you leave. Did you know that your cast-off emotions, your misjudged encounters and mistaken affairs, were precious enough to be my very being? Your follies, failings, your loud drunken songs. All of these I have taken to heart, and I care about you all. Have never wanted you to feel pain, to hurt yourselves or one another, but like the timid older relative I feel myself to be, I can’t stop any of these things. Only you can do that.

And you do, most of you. The days are longer than the nights for half the year, and then you pass in greater numbers. Mothers, singing to their babies, people talking to their dogs, and older feet that go more slowly, clicking sticks between the steps, and breathing laboured, but the same affection for the town, its stones and passages, its alleyways. The jitties.

Still the children keep coming, on the walk to school and back, hatching plots and learning these ways through their town, the ways they’ll walk for decades, choosing jitty over pavement, quiet shade over traffic and noise. You see, like a jitty, this works in both directions. The people leave their traces here, and these become me. But the jitties shape the people who pass along them, making them to some degree as I am, shy and furtive, unkeen to be seen, afeared to be heared, not wanting notice. So all of you – some more than others – have jitty inside you. How else could it be? I am a part of you, just as my parts are yours. I’ll be here as long as there are jitties, and people walking. They never stop walking. Here comes a boy, not five years old or else he’d be at school, trotting ahead of the lady he’s about to call Granny. Listen.

‘Granny?’ Stops and turns, waiting for her.

‘Yes, duck.’ Hand on the handsmoothed rail.

‘I love this passageway.’ Puts her other hand down to his shoulder.

‘Jitty, duck. It’s called a jitty.’